[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Signs & Symptoms | Mechanisms of Injury | Diagnosis | Prevention | Treatment | Conservative | Surgery | Rehabilitation

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

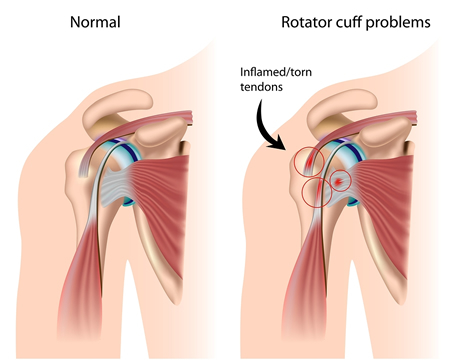

A rotator cuff tear is a tear of one or more of the tendons of the four rotator cuff muscles of the shoulder. A rotator cuff ‘injury’ can include any type of irritation or overuse of those muscles or tendons, and is among the most common conditions affecting the shoulder.

A rotator cuff tear is a tear of one or more of the tendons of the four rotator cuff muscles of the shoulder. A rotator cuff ‘injury’ can include any type of irritation or overuse of those muscles or tendons, and is among the most common conditions affecting the shoulder.

The tendons of the rotator cuff, not the muscles, are most commonly involved, and of the four, the supraspinatus is most frequently affected, as it passes below the acromion. Such a tear usually occurs at its point of insertion onto the humeral head at the greater tubercle.

The cuff is responsible for stabilizing the glenohumeral joint, abducting, externally rotating, and internally rotating the humerus. When shoulder trauma occurs, these functions can be compromised. Because individuals are highly dependent on the shoulder for many activities, overuse of the muscles can lead to tears, the vast majority again occurring in the supraspinatus tendon.

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Signs and Symptoms

Many rotator cuff tears are asymptomatic. They are known to increase in frequency with age and the most common cause is age-related degeneration and, less frequently, sports injuries or trauma. Both partial and full thickness tears have been found on post mortem and MRI studies in those without any history of shoulder pain or symptoms. However, the most common presentation is shoulder pain or discomfort. This may occur with activity, particularly shoulder activity above the horizontal position, but may also be present at rest in bed. Pain-restricted movement above the horizontal position may be present, as well as weakness with shoulder flexion and abduction.

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Mechanisms of injury

The two main causes are injury (acute) and degeneration (chronic and cumulative), and the mechanisms involved can be either extrinsic or intrinsic or, probably most commonly, a combination of both.

Acute tears

The amount of stress needed to tear a rotator cuff tendon acutely will depend on the underlying condition of the tendon prior to the stress. In the case of a healthy tendon, the stress needed will be high, such as a fall on the outstretched arm. This stress may occur coincidentally with other injuries such as a dislocation of the shoulder, or separation of the acromioclavicular joint. In the case of a tendon with pre-existing degeneration, the force may be surprisingly modest, such as a sudden lift, particularly with the arm above the horizontal position. This is a common occurrence with rear seated passengers in a motor vehicle collision, regardless of speed.

Chronic tears

Chronic tears are indicative of extended use in conjunction with other factors such as poor biomechanics or muscular imbalance. Ultimately, most are the result of wear that occurs slowly over time as a natural part of aging. They are more common in the dominant arm, but a tear in one shoulder signals an increased risk of a tear in the opposing shoulder. Several factors contribute to degenerative, or chronic, rotator cuff tears of which repetitive stress is the most significant. This stress consists of repeating the same shoulder motions frequently, such as overhead throwing, rowing, and weightlifting. Many jobs that require frequent shoulder movement such as lifting and overhead movements also contribute.

Another factor in older populations is impairment of blood supply. With age, circulation to the rotator cuff tendons decreases, impairing natural ability to repair, ultimately leading to, or contributing to, tears.

The final common factor is impingement syndrome, the most common nonsports-related injury and which occurs when the tendons of the rotator cuff muscles become irritated and inflamed while passing through the subacromial space beneath the acromion. This relatively small space becomes even smaller when the arm is raised in a forward or upward position. Repetitive impingement can inflame the tendons and bursa, resulting in the syndrome.

Extrinsic factors

Well-documented anatomical factors include the morphologic characteristics of the acromion. Hooked, curved, and laterally sloping acromia are strongly associated with cuff tears and may cause tractional damage to the tendon.[10] Conversely, flat acromia may have an insignificant involvement in cuff disease and consequently may be best treated conservatively. The development of these different acromial shapes is likely both genetic and acquired. In the latter case, only age has been positively correlated with progression from flat to curved or hooked. The nature of mechanical activities, such as sports involving the shoulder, along with frequency and intensity of such sports, may be responsible for the adverse development. Sports such as bowling in cricket, swimming, tennis, baseball, and kayaking, are most frequently implicated. However, a progression to a hooked acromion may simply be an adaptation to an already damaged, poorly balanced rotator cuff that is creating increasing stress on the coracoacromial arch. Other anatomical factors that may have significance include os acromiale and acromial spurs. Environmental factors implicated include increasing age, shoulder overuse, smoking, and any medical condition that affects circulation or impairs the inflammatory and healing response, such as diabetes mellitus.

Intrinsic factors

Intrinsic factors refer to injury mechanisms that occur within the rotator cuff itself. The principal is a degenerative-microtrauma model, which supposes that age-related tendon damage compounded by chronic microtrauma results in partial tendon tears that then develop into full rotator cuff tears. As a result of repetitive microtrauma in the setting of a degenerative rotator cuff tendon, inflammatory mediators alter the local environment, and oxidative stress induces tenocyte apoptosis causing further rotator cuff tendon degeneration. A neural theory also exists that suggests neural overstimulation leads to the recruitment of inflammatory cells and may also contribute to tendon degeneration.

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based upon physical assessment and history, including description of previous activities and acute or chronic symptoms. A systematic, physical examination of the shoulder comprises inspection, palpation, range of motion, provocative tests to reproduce the symptoms, neurological examination, and strength testing. The shoulder should also be examined for tenderness and deformity. Since pain arising from the neck is frequently ‘referred’ to the shoulder, the examination should include an assessment of the cervical spine looking for evidence suggestive of a pinched nerve, osteoarthritis, or rheumatoid arthritis.

Diagnostic modalities, dependent on circumstances, include X-ray, MRI, MR arthrography, double-contrast arthrography, and ultrasound. Although MR arthrography is currently considered the gold standard, ultrasound may be most cost-effective. Usually, a tear will be undetected by X-ray, although bone spurs, which can impinge upon the rotator cuff tendons, may be visible. Such spurs suggest chronic severe rotator cuff disease. Double-contrast arthrography involves injecting contrast dye into the shoulder joint to detect leakage out of the injured rotator cuff and its value is influenced by the experience of the operator. The most common diagnostic tool is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which can sometimes indicate the size of the tear, as well as its location within the tendon. Furthermore, MRI enables the detection or exclusion of complete rotator cuff tears with reasonable accuracy and is also suitable to diagnose other pathologies of the shoulder joint.

The logical use of diagnostic tests is an important component of effective clinical practice. X-rays cannot directly reveal tears of the rotator cuff, a ‘soft tissue’, and consequently, normal X-rays cannot exclude a damaged cuff. However, indirect evidence of pathology may be seen in instances where one or more of the tendons have undergone degenerative calcification (calcific tendinitis). Also, large tears of the rotator cuff may allow the humeral head to migrate upwards (high-riding humeral head) which may be visible on X-ray. Prolonged contact between a high-riding humeral head and the acromion above it, may lead to X-rays findings of wear on the humeral head and acromion and secondary degenerative arthritis of the glenohumeral joint (the ball and socket joint of the shoulder), called cuff arthropathy, may follow. Incidental X-ray findings of bone spurs at the adjacent acromioclavicular joint may show a bone spur growing from the outer edge of the clavicle downwards towards the rotator cuff. Spurs may also be seen on the underside of the acromion, once thought to cause direct fraying of the rotator cuff from contact friction, a concept currently regarded as controversial.

Clinical judgement, rather than over reliance on MRI or any other modality, is strongly advised in determining the cause of shoulder pain, or planning its treatment, since rotator cuff tears are also found in some without pain or symptoms. The role of X-ray, MRI, and ultrasound, is adjunctive to clinical assessment and serves to confirm a diagnosis provisionally made by a thorough history and physical examination. Over-reliance on imaging may potentially lead to overtreatment or distraction from the true underlying problem.

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Prevention

Long-term overuse/abuse of the shoulder joint is generally thought to limit range of motion and productivity due to daily wear and tear of the muscles, and many public web sites offer preventive advice. The recommendations usually include:

- regular shoulder exercises to maintain strength and flexibility

- using proper form when lifting or moving heavy weights

- resting the shoulder when experiencing pain

- application of cold packs and heat pads to a painful, inflamed shoulder

- strengthening program to include the back and shoulder girdle muscles as well as the chest, shoulder and upper arm

- adequate rest periods in occupations that require repetitive lifting and reaching

Size

According to a study which measured tendon length against the size of the injured rotator cuff, researchers learned that as rotator cuff tendons decrease in length, the average rotator cuff severity is proportionally decreased, as well. This shows that larger individuals are more likely to suffer from a severe rotator cuff tear if they do not tighten the shoulder muscles around the joint.

Position

Another study observed 12 different positions of movements and their relative correlation with injuries occurred during those movements. The evidence shows that putting the arm in a neutral position relieves tension on all ligaments and tendons.

Stretching

One article observed the influence of stretching techniques on preventative methods of shoulder injuries. Increased velocity of exercise increases injury, but beginning a fast-movement exercise with a slow stretch may cause muscle/tendon attachment to become more resistant to tearing.

Muscle groups

When exercising, exercising the shoulder as a whole and not one or two muscle groups is also found to be imperative. When the shoulder muscle is exercised in all directions, such as external rotation, flexion, and extension, or vertical abduction, it is less likely to suffer from a tear of the tendon.

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Treatment

Those suspected of having a rotator cuff tear are potentially candidates for either operative or non-operative (conservative) treatment. However, any individual may move from one group to the other based on clinical response and findings on repeated examination.

No evidence of benefit is seen from early rather than delayed surgery, and many with partial tears and some with complete tears will respond to non-operative management. Consequently, many recommend initial, nonsurgical management. However, early surgical treatment may be considered in significant (>1 cm-1.5 cm) acute tears or in young patients with full-thickness tears who have a significant risk for the development of irreparable rotator cuff changes.

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Conservative

Those with pain but reasonably maintained function are suitable for nonoperative management. This includes oral medications that provide pain relief such as anti-inflammatory agents, topical pain relievers such as cold packs, and if warranted, subacromial corticosteroid/local anesthetic injection. A sling may be offered for short-term comfort, with the understanding that undesirable shoulder stiffness can develop with prolonged immobilization. Early physical therapy may afford pain relief with modalities (e.g. iontophoresis) and help to maintain motion. Ultrasound treatment is not efficacious. As pain decreases, strength deficiencies and biomechanical errors can be corrected.

A conservative physical therapy program begins with preliminary rest and restriction from engaging in activities which gave rise to symptoms. Normally, inflammation can usually be controlled within one to two weeks, using a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and subacromial steroid injections to decrease inflammation, to the point that pain has been significantly decreased to make stretching tolerable. After this short period, rapid stiffening and an increase in pain can result if sufficient stretching has not been implemented.

A gentle, passive range-of-motion program should be started to help prevent stiffness and maintain range of motion during this resting period. Exercises, for the anterior, inferior, and posterior shoulder, should be part of this program. The use of NSAIDs, hot and cold packs, and physical therapy modalities, such as ultrasound, phonophoresis, or iontophoresis, can be instituted during this stretching period, if effective. Corticosteroid injections are recommended two to three months apart with a maximum of three injections. Multiple injections (four or more) have been shown to compromise the results of rotator cuff surgery which result in weakening of the tendon. However, before any rotator cuff strengthening can be started, the shoulder must have a full range of motion.

After a full, painless range of motion is achieved, the patient may advance to a gentle strengthening program. This program is aimed at creating an exercise regimen that initially gently improves motion, then gradually improves strength in the shoulder girdle.

Several instances occur in which nonoperative treatment would not be suggested:

- 20 to 30-year-old active patient with an acute tear and severe functional deficit from a specific event

- 30 to 50-year-old patient with an acute rotator cuff tear secondary to a specific event

- a highly competitive athlete who is primarily involved in overhead or throwing sports

These patients may need to be treated operatively because rotator cuff repair is necessary for restoration of the normal strength required to return to the preoperative, competitive level of function. Finally, those who do not respond to, or are unsatisfied with, conservative treatment should seek a surgical opinion.

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Surgery

The three general surgical approaches are arthroscopic, mini open, and open-surgical repair. In the recent past, small tears were treated arthroscopically, while larger tears would usually require an open procedure. Advances in arthroscopy now allow arthroscopic repair of even the largest tears, and arthroscopic techniques are now required to mobilize many retracted tears. The results match open surgical techniques, while permitting a more thorough evaluation of the shoulder at time of surgery, increasing the diagnostic value of the procedure, as other conditions may simultaneously cause shoulder pain. Arthroscopic surgery also allows for shorter recovery time although significant differences in postoperative pain or pain medication use apparently are not seen between arthroscopic- and open-surgical patients.

Even for full-thickness rotator cuff tears, conservative care (i.e., nonsurgical treatment) outcomes are usually reasonably good. However, many patients still suffer disability and pain despite nonsurgical therapies. For massive tears of the rotator cuff, surgery has shown durable outcomes on 10-year follow-up. However, the same study demonstrated ongoing and progressive fatty atrophy and repeat tears of the rotator cuff. MRI evidence of fatty atrophy in the rotator cuff prior to surgery is predicative of a poor surgical outcome. If the rotator cuff is completely torn, surgery is usually required to reattach the tendon to the bone.

If a significant bone spur is present, any of the approaches may include an acromioplasty, a subacromial decompression, as part of the procedure. Subacromial decompression, removal of a small portion of the acromion that overlies the rotator cuff, aims to relieve pressure on the rotator cuff in certain conditions and promote healing and recovery. Although subacromial decompression may be beneficial in the management of partial and full-thickness tear repair, it does not repair the tear itself and arthroscopic decompression has more recently been combined with “mini-open” repair of the rotator cuff, allowing for the repair of the cuff without disruption of the deltoid origin. The results of decompression alone tend to degrade with time, but the combination of repair and decompression appears to be more enduring.

Repair of a complete, full-thickness tear involves tissue suture. The method currently in favor is to place an anchor in the bone at the natural attachment site, with resuture of torn tendon to the anchor. If tissue quality is poor, mesh (collagen, Artelon, or other degradable material) may be used to reinforce the repair. Repair can be performed through an open incision, again requiring detachment of a portion of the deltoid, while a mini-open technique approaches the tear through a deltoid-splitting approach. The latter may cause less injury to muscle and produce better results. Contemporary techniques now use an all arthroscopic approach. Recovery can take as long as three–six months, with a sling being worn for the first one–six weeks.

In a small minority of cases where extensive arthritis has developed, an option is shoulder joint replacement (arthroplasty).

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation after surgery consists of three stages. First, the arm is immobilized so that the muscle can heal. Second, when appropriate, a therapist assists with passive exercises to regain range of motion. Third, the arm is gradually exercised actively, with a goal of regaining and enhancing strength.

Following arthroscopic rotator-cuff repair surgery, patients undergo rehabilitation to regain shoulder function. Orthopaedic surgeons stress that physical therapy is crucial to healing. Exercises decrease shoulder pain, strengthen the joint, and improve the arm’s range of motion. Therapists, in conjunction with the surgeon, design workout regimens in accordance with individuals’ needs and risk factors.

Traditionally, patients have been advised to immobilize their shoulders for six weeks before doing rehabilitation. However, the appropriate timing and intensity of therapy are subject to debate. Regardless, most surgeons advocate to remain in the sling for at least six weeks. Some authorities advocate early, aggressive rehab. They favor the use of passive motion, which allows a patient to move the shoulder without physical effort. Alternatively, some authorities argue that therapy should be started later and carried out more cautiously. Theoretically, that gives tissues time to heal; though there is conflicting data regarding the benefits of early immobilization. A study of rats suggested that it improved the strength of surgical repairs, while research on rabbits produced contrary evidence. Patients, especially those recovering from large rotator cuff tears, are prone to developing new tears. Rehabbing too soon or too strenuously might increase the risk of retear or failure to heal. However, no research has proven a link between early therapy and the incidence of re-tears. In some studies, patients who received earlier and more aggressive therapy reported reduced shoulder pain, less stiffness and better range of motion. Other research has shown that accelerated rehab results in better shoulder function. Despite the findings, “no definitive consensus exists supporting a clinical difference” between the two methods of rehab.

There is consensus amongst orthopaedic surgeons and physical therapists regarding rotator cuff repair rehabilitation protocols. The timing and duration of treatments and exercises are based on biologic and biomedical factors involving the rotator cuff. For approximately two to three week following surgery, a patient experiences shoulder pain and swelling; no major therapeutic measures are instituted in this window other than oral pain medicine and ice. All in all, those patients at risk of failure, should undergo a more conservative approach to rehabilitations.

That is followed by the “proliferative” and “maturation and remodeling” phases of healing, which ensues for the following six to ten weeks. The effect of active or passive motion during any of the phases is unclear, due to conflicting information and a shortage of clinical evidence. Gentle physical therapy guided motion is instituted at this phase, only to prevent stiffness of the shoulder; the rotator cuff remains fragile. At three months after surgery, physical therapy intervention changes substantially to focus on scapular mobilization and stretching of the glenohumeral joint. Once full passive motion is regained (at usually about four to four and a half months after surgery) strengthening exercises are the focus. The strengthening focuses on the rotator cuff and the upper back/scapular stabilizers. Typically at about six months after surgery, most patients have made a majority of the gains.

Due to the conflicting information about the relative benefits of rehab conducted early or later, an individualized approach is necessary. The timing and nature of therapeutic activities are adjusted according to patients’ ages, the tissue integrity of their rotator cuff repairs and other factors. Special considerations are appropriate for those who have suffered multiple tears.

[/av_textblock]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Our Shoulder Doctors:

| Dr. James Ferrari | Dr. Wayne Gersoff | Dr. Andrew Motz |

| Dr. Justin Newman | Dr. John Papilion | Dr. Micah Worrell |

[/av_textblock]

[av_one_full first first min_height=” vertical_alignment=’av-align-top’ space=” margin=’0px’ margin_sync=’true’ padding=’20px’ padding_sync=’true’ border=” border_color=” radius=’0px’ radius_sync=’true’ background_color=’#e0e0e0′ src=” attachment=” attachment_size=” background_position=’top left’ background_repeat=’no-repeat’ animation=”]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Source

Content provided by Wikipedia

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License

[/av_textblock]

[/av_one_full]

[av_social_share title=’Share this entry’ style=” buttons=” share_facebook=” share_twitter=” share_pinterest=” share_gplus=” share_reddit=” share_linkedin=” share_tumblr=” share_vk=” share_mail=”][/av_social_share]